Kabul, Afganistan

Words & Photography: Andrew Quilty

Words & Photography: Andrew Quilty

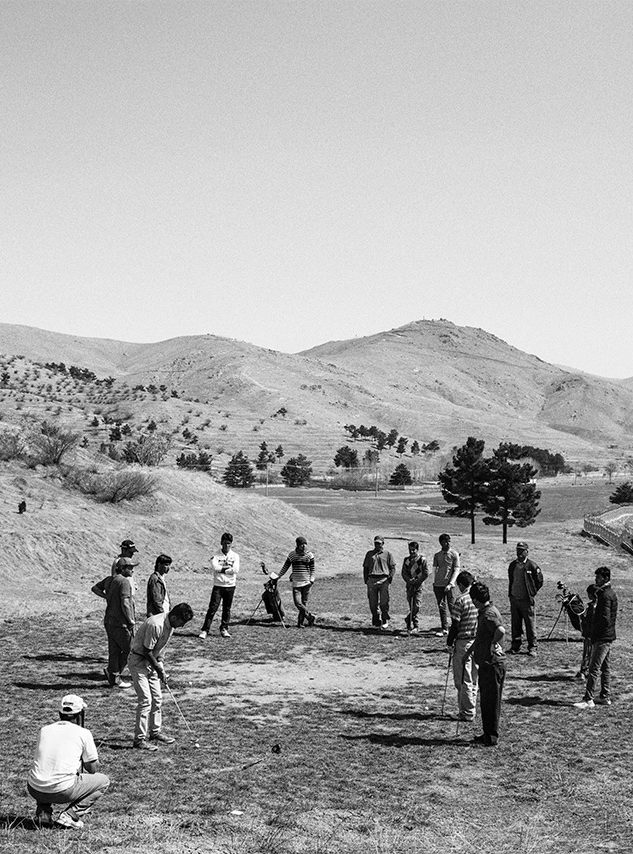

Andrew Quilty takes a stroll with the locals through the golfing scene at Kabul Golf Club.

Story cover image: Ali, on the fairway with his teammate Jawad (far left) at Kabul Golf Club, on the Afghan capital’s western outskirts

When Mohammad Afzal Abdul returned to Afghanistan after the fall of the Taliban, he went straight to the golf course he’d first swung a club on at the age of eight. Located in a shallow valley of grey grass on the edge of Kabul, the golf course – from which Afzal, now 55, had fled ten years earlier to seek refuge in neighbouring Pakistan – was barely recognisable.

“The grass was up to here,” Afzal says, pointing to his thigh and the trees that once lined the fairways that had been felled for firewood by those who’d remained behind during the civil war of the early 1990s, and the Taliban rule that followed.

The biggest problem, however, was the likelihood that the course was now littered with unexploded ordnance and landmines. “There were many rockets falling in this area,” he recalls of the time before he fled.

Impatient to bring Afghanistan’s only golf course back to life, Afzal found an unusual way to dispose of the mines: he opened the gates and the sumptuous, grassy fairways to local shepherds and their flocks of sheep. “They didn’t know what was going on,” he laughs, inside the Kabul Golf Club’s single-room clubhouse on a gloomy afternoon. Seeing a sheep or two blown apart by an anti-personnel mine would be preferable to a dead golfer, he thought.

The following decade of international military intervention saw the Afghan capital awash with foreign aid workers, diplomats, security contractors, and American dollars. Even though it was far from the centre of the city where most foreigners were cloistered, for ten years the novelty of playing golf in Afghanistan drew a steady stream of enthusiasts to Kabul Golf Club (KGC) after its official opening in 2004.

Some would return home from holidays with clubs salvaged from storage units and donate them to Afzal and a small but passionate group of golfers from the surrounding villages. With the mismatched clubs that accumulated, keen young locals Hamidullah, Jawad and Ali managed to whittle their handicaps down to single figures.

The twenty-somethings play the 9 hole, par-36 course religiously – while much of the rest of Kabul prays – on Friday mornings. Their attire is as eclectic as their selection of clubs: Jawad wears a Titleist cap, a TaylorMade polo shirt and golf spikes; Hamidullah, track pants and street shoes. They play throughout the warmer months with a handful of others whose scrappy swings belie entirely respectable scores.

Proper putting surfaces have never been within financial reach of Afzal’s low budget operation, and for many years, with typical Afghan ingenuity, his jerry-rigged ‘greens’ made use of the few resources available – a compacted mixture of engine oil and sand.

Despite the club’s donated ride-on lawn mower, the fairways were always so patchy that repositioning one’s lie to the nearest clump of grass has always been tolerated. As Hamidullah puts it, from what he’s seen on television, “an American course is like walking on carpet; here it’s like walking on splinters”.

In 2014, the vast majority of foreign soldiers in Afghanistan withdrew from combat operations. Although international leaders declared that Afghanistan was ready to stand on its own two feet, since then the country has struggled with a faltering economy and a resurgent Taliban. Not to mention the rise of ISIS, which has claimed several devastating attacks, including a suicide bombing that took at least 80 lives at a peaceful protest in Kabul.

The KGC, like the rest of the country, has suffered. Afzal claims he hasn’t had a foreigner play “since [President] Karzai’s time” – before 2014. He can no longer afford his oil and sand green treatment and so the putting surfaces are barely discernible from the fairways. On the green, players tamp down their paths to the hole with their putters.

The most committed players, like Hamidullah, can’t afford the green fees. Resigned to the new reality, Afzal allows them to play for free. He says around 100 people play for free each week, while sometimes “rich Afghans” pay 1000 Afghani ($AU20) – a far cry from the US$50 fee foreigners used to pay.

By midday on Fridays the course is crowded. To Afzal and his acolytes’ dismay, however, it isn’t golfers populating the fairways. Young families picnic; groups of young men play cricket and soccer; while local warlords stroll along the road that runs like a spine through the centre of the KGC, enjoying the relative security of the fenced-off course with their Kalashnikov-toting bodyguards in tow. The golfers have little choice but to call it a day after nine holes.

With their golf clubs locked up inside the clubhouse, another KGC regular, Noor Ahmad, offers to walk with me to a hilltop high to the west, where an abandoned tank – a relic of the Soviet war of the 1980s – looms over the course. The barrel of its canon points toward the 3rd tee in the valley below.

Once we’ve negotiated our way back down the mountainside, walking back along the road between fairways, Ahmad remonstrates with a young girl carrying a large rock that was protecting a sprinkler valve. She plans to use it as a wicket for her family’s cricket match. A minute later, he’s banging on a car window as the driver chews up the fairway trying to park his car. “They don’t even realise this is a golf course.”

Words and Photography by Walkley Award winning Australian photographer Andrew Quilty.

This story was originally published in Volume Two of Caddie Magazine. Volume Two will sell out, and will never be reprinted. Caddie Magazine is 100% independent and relies on subscriptions to create stories like this. To support Caddie and independent publishing please subscribe or even better, Go All In.

No images shown on this page may be used, republished or reproduced in any way without permission directly from the photographer.